SEASON 8 | CURATORIAL STATEMENT

Season 8 of The Centre for the Less Good Idea was curated by performer, musician, writer, and educator Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu, and used the provocations of Breath & Mythology to produce a programme of new collaborative, experimental, and interdisciplinary work.

The performances that make up Season 8’s programme of work prize the musical, the physical and the narrative, and are equal parts humorous, absurd and contemplative. Additionally, a multi-media exhibition was on show for the duration of the Season. Titled Thinking in Poetry and Cardboard, the exhibition serves as an archive of process for both the SO Academy’s Thinking in Cardboard mentorship programme, and the The Khala Series 2021 | 100 Poem Project, curated by poet Upile Chisala.

PROVOCATION 1 | BREATHE & BREATHING AGAIN

A Season of work prompted in part by the activity of breathing might seem an obvious choice now, but harnessing breath as a provocation for Season 8 of the Centre was a decision made prior to the global Covid-19 pandemic.

In this way, many of the works in this Season feel both prophetic and sharply relevant, musing on the absence of breath and the tentative or revelatory act of breathing once more. That said, there is also a conscious effort to refuse the overt and ready interpretations of the theme, opting instead to pursue its abstractions and lesser-known understandings. There is breath as necessity, as music, language, loss, presence, and more.

Breath has also played a vital role in the daily warm-ups and overall structure of the preliminary workshops that preceded this Season of work, and has influenced much of the thinking behind the performances. There is the idea of revitalising forgotten or erased figures and histories, and an attempt at understanding our preoccupation with breath in relation to work and process – breath control, letting a text breathe, or breathing new life into old ideas.

Finally, there is much meditation on the relationship between breath and the body, and how we both care for and relate to our bodies – and the bodies of others – during a period where the notion of breath is perhaps more crucial than ever before.

PROVOCATION 2 | MYTHOLOGY

Where do folktales, narratives, taboos, and legends originate? How do they influence our ways of making sense of the world? Rather than seeking to address these questions directly, Season 8 engages the varying forms and functions of myth, and has, at its core, a preoccupation with mythology both ancient and contemporary.

Drawing on notions of religion, spirituality, imagination, personal mythology and more, this Season’s works were tested and generated through the stage, the page, and the movement of the body. As a result, many of the works in the Season locate mythology in one’s personhood, upbringing, culture, and heritage. They span the monstrous, the magical, the political, the ceremonial, and the allegorical while holding a keen interest in the translation and reading of mythology across language, site, and identity.

While the provocation is a serious one that lends a solemn underpinning to much of the work, there is also a commitment to the humorous, the joyful, the fantastical and the absurd in equal measure. In the tradition of The Centre, many of these works embrace the methodology of performance in process, and pursue the secondary, the incidental, and the emergent idea.

PRODUCTION FOR THE CENTRE

CURATOR

Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu

LEAD DIRECTOR

Faniswa Yisa

ARTISTIC ADVISOR

Nhlanhla Mahlangu

PARTICIPANTS

Ayanda Seoka

Calvin Seretle Ratladi

Clare Loveday

Iman Isaacs

Katlego KayGee Letsholonyane

Khanyisile Ngwabe

Micca Manganye

Macaleni Muzi Shili

Sibahle Mangena

Sinenhlanhla Prince Mgeyi

Siphumeze Khundayi

Thabo Rapoo

Thembinkosi Mavimbela

Thulisile Binda

Zarcia Zacheus

ANIMATEUR | Phala Ookeditse Phala

CO-DIRECTOR | Bronwyn Lace

MOMENTEUR FOR THE SO ACADEMY | Athena Mazarakis

DIRECTOR OF CINEMATOGRAPHY & EDITING | Noah Cohen

SOUND ENGINEER | Zain Vally

ADMINISTRATOR, PROJECT MANAGER & HEAD STAGE MANAGER | Dimakatso Motholo

STAGE MANAGER | Nthabiseng Malaka

HOUSEKEEPING & SPACE MANAGER | Gracious Dube

PHOTOGRAPHER

Zivanai Matangi

EDITOR

Noah Cohen

COSTUME & SET DESIGNERS

Nthabiseng Malaka

Natalie Paneng

SOUND ENGINEERS

Zain Vally

Ross Culverwell

Daev Moyo

CINEMATOGRAPHERS

Noah Cohen

JUNIOR CINEMATOGRAPHER

Bukhosibakhe Kelvin Khosa

LIVESTREAM ENGINEER

Chris-Waldo de Wet

LIGHTING DESIGNER

Wesley France

LIGHTING TECHNICIANS & OPERATORS

Matthews Phala

Themba Mthimkulu

Bongani Mpofu

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

Smangaliso Ngwenya

PROGRAMME DESIGNER

Phala O. Phala

WRITER

David Mann

PUBLICITY

Azania Public

POPArt Productions

FRONT OF HOUSE

POPArt Productions:

Hayleigh Evans

Dintshitile Mashile

Khanyisile Zwane

Rethabile Headbush

Emil Lars

Ncumisa Ndimeni

With The Market Theatre Lab 2nd Year Students:

Kefenste Mokoena, Lungile Mabaso, Zevangeli Mpofu, Onakho Hlanti, Omolemo Magabe, Nomcebo Khonoti, Mthobisi Gasa, Aviwe Dasha, Lerato Ndlovu, Nhlanhla Sadiki, Muzi Trust, Buntu Ceza & Thato Mosebi

LIGHTING GEAR SUPPLIER

Gearhouse Splitbeam (Pty) Ltd

STAGING SUPPLIER

Setsational

SOUND EQUIPMENT SUPPLIER

SoulFire Studio (Pty) Ltd

Special thanks:

Linda Leibowitz, Natalie Dembo, Anne McIlleron, Anne Blom, Joy Woolcott, Chris-Waldo de Wet, Jacques van Staden, Joey Netshiombo, Diego Sillands & Thandi Mzizi Nkabinde

SONG CYCLE

A musical performance featuring three original compositions, Song Cycle is a work that explores notions and activities of passivity, erasure, desire, and the importance of naming those forgotten women figures in mythological history.

It Is Best, composed by Clare Loveday and featuring text by Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu, opens the performance with a playful and contemplative dialogue between music (Lecoge-Zulu on flute) and text (Zarcia Zacheus on vocals). It’s a playful and engaging composition that experiments time and breath, both musically and in terms of their location in Season 8’s broader themes and provocations.

Following this, It Is Better Not To Be Seen sees Thembinkosi Mavimbela and Micca Manganye join Zacheus on stage. Mavimbela’s basswork is gentle and considered, while Manganye lends a deliberate percussion, as well as a lively multi-instrumentalism to the performance. Again, Zacheus’ vocals are delivered with a close attention to wordplay, building up to a brief, but powerful solo from Mavimbela before the song reaches a slow and gentle conclusion.

For the third and final song, Yemaja, Mavimbela brings out the upright bass, while Manganye introduces shakers to his steady percussion. Zacheus holds a firm and resonant refrain – a rallying call to the chorus who begin offstage and gradually join the trio. The result is a full and rich performance, punctuated by well-placed notes from Lecoge-Zulu’s flute. As the closing song, the performance swells and charges the space, its call-and-response style composition breaching the borders of the stage and reaching out to involve the audience.

All three songs, original collaborative compositions generated over the course of Season 8, reckon with the key provocations of the Season – that of breath and mythology – and serve to puzzle out, through performance and play, the broader themes of text, music, and their inherent relationships with language and the body.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

COMPOSERS | Yemaja by Zarcia Zacheus & Thembinkosi Mavimbela, It Is Better Not To Be Seen by Zarcia Zacheus, Thembinkosi Mavimbela & Clare Loveday, It Is Best by Clare Loveday & text by Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu

PERFORMERS | Zarcia Zacheus, Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu, Micca Manganye, Thembinkosi Mavimbela & Chorus

IN OUT & ABOVE

Bodies and instruments alike are performed through In Out & Above, a performance that merges music and physicality in striking and novel ways.

Charged with tension, In Out & Above mines the inherent narrative of the body, and muses on the dynamic between one’s practice and core self. There is a drum, but it is not played. This predicament – this expectation of music – quickly falls away when the two performers begin a conversation between stilted movement (Manganye) and free-flowing, but responsive choreography (Shili).

As the performance progresses, the two become increasingly intertwined. Shili circles Manganye, climbs him, lays upon him, both disrupting and informing his relationship with his instrument and his own body. Manganye pushes through, giving way to an extraordinary display of physical and musical performance. Together, they build and sustain a compelling display of struggle and tension. As Shili anchors himself, supine and unmoving on the musician’s lap, Manganye endures, raising his tired arms to beat out a steady and laboured rhythm.

Ultimately, music and body become interwoven, both literally and figuratively, through a pursuit of the inner-self. Manganye and Shili’s fraught and fated relationship finds resonance in an arduous but unified procession off stage – all limbs and hands and a heavy, deliberate gait – leaving only the drum and an empty chair behind.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISER & CHOREOGRAPHER | Muzi Shili

DIRECTOR | Thabo Rapoo

PERFORMERS | Muzi Shili & Micca Manganye

BASSLEXIA

Basslexia, performed by Faniswa Yisa and Thembinkosi Mavimbela, sits deliberately and overtly at the intersection of Western and African understandings of music.

Mavimbela, representing Western music, approaches his double bass, donned in a full suit. Yisa, representing African music, sits off to the side of the stage. There is a lecture – a history of the instrument by Mavimbela – followed by a brief performance. Yisa, sceptical and reserved, approaches and begins to translate, both revising and parodying Mavimbela’s engagement with the instrument. This gives way to a moment of instruction, a rich and reflective scene of clashing style and interpretation. What emerges is a deviation, a reimagining of a single instrument approached through varying histories, methodologies and practices.

The resultant performance is a kind of exquisite tension – a union that refuses neat harmony and composition. It is a puzzling out of the disparities between knowledge and education, tradition and custodianship.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISER | Thembinkosi Mavimbela

DIRECTOR | Nhlanhla Mahlangu

PERFORMERS | Thembinkosi Mavimbela & Faniswa Yisa

PITSANA

It begins with a crash. A woman emerges (Thulisile Binda), carrying the fallen pot and a steaming plate of food. Once recomposed, she delivers the blistering plate to an indifferent man (Thabo Rapoo) who begins to eat, silently and without thanks. A narrator seated to the left (Ayanda Seoka) provides a spoken narrative, delivered in a cold and detached tone while the sounds of the double bass (Thembinkosi Mavimbela) lend a sobering sensibility to the scene.

The woman approaches the boiling pot, lifts the lid above her head and steps into its red-hot contents. It is a moment of acute agony, repeated to the point of torment. She screams, jerks this way and that, endures. There is the high, whiny pitch of pain, as well as the ever-boiling pot, animated by the percussive and vocal work of a two-person chorus (Micca Manganye and Muzi Shili), situated to the back of the stage. All the while, Rapoo sits and eats, oblivious to her pain, ignorant of the bristling resentment, the boiling over of history, emotion and power.

At last, a moment of defiance and catharsis comes in the form of the burned and blistered foot, raised high and brought down on the plate of food. There is only silence, then, followed by the shirking of the lid, a final gesture that leaves the sharp metallic crash ringing through the room.

Pitsana is a performance that grapples with the conventions of responsibility, duty, and labour. It is a story that posits the consequences of a physical and psychological repression of energy.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISER & CHOREOGRAPHER | Thulisile Binda

DIRECTOR | Phala O. Phala

MUSICIANS | Thembinkosi Mavimbela, Micca Mangaye & Muzi Shili

PERFORMERS | Thabo Rapoo, Thulisile Binda, Ayanda Seoka, Muzi Shili & Thembinkosi Mavimbela

TORO

The closing performance of Season 8’s debut programme, Toro occupies a state of dreamlike incoherence and plays with the notions of sight, communication, breath, mythology, lucidity and more through a feverish and immersive ensemble work.

One by one, they occupy the stage. There is laughter, shrieking, obscured faces, disparate music, and ominous visages. Absurdity and humour, too. In and amongst the fray, there is the repeated scenario of being caught with one’s pants down, while a carboard box on legs fumbles about the stage. The overall scene builds and grows, becomes something of a nightmare ensemble, a hazy and intangible cacophony of fears, dreams, places and faces. A character emerges, stands centre stage and flips forward, landing with a crash that’s loud enough to break the fever-pitch of sound and activity.

A seamless segue into abstraction takes place. It is a move further towards the incoherent and the unresolved, although this time with a sobering air. A single voice emerges, sounding out from the corner of the stage. The lights fade and give way to a haunting lucidity before fading to black, a deep, long sleep held only by the silence.

- David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISERS & PERFORMERS | Zarcia Zacheus, Siphumeze Khundayi, Calvin Ratladi, Iman Isaacs, Faniswa Yisa, Sinenhlanhla Mgeyi, Ayanda Seoka, Katlego KayGee Letsholonyane, Micca Manganye, Sibahle Mangena, Thabo Rapoo, Thembinkosi Mavimbela, Thulisile Binda, Khanyisile Ngwabe & Muzi Shili

WHAT IS IT?

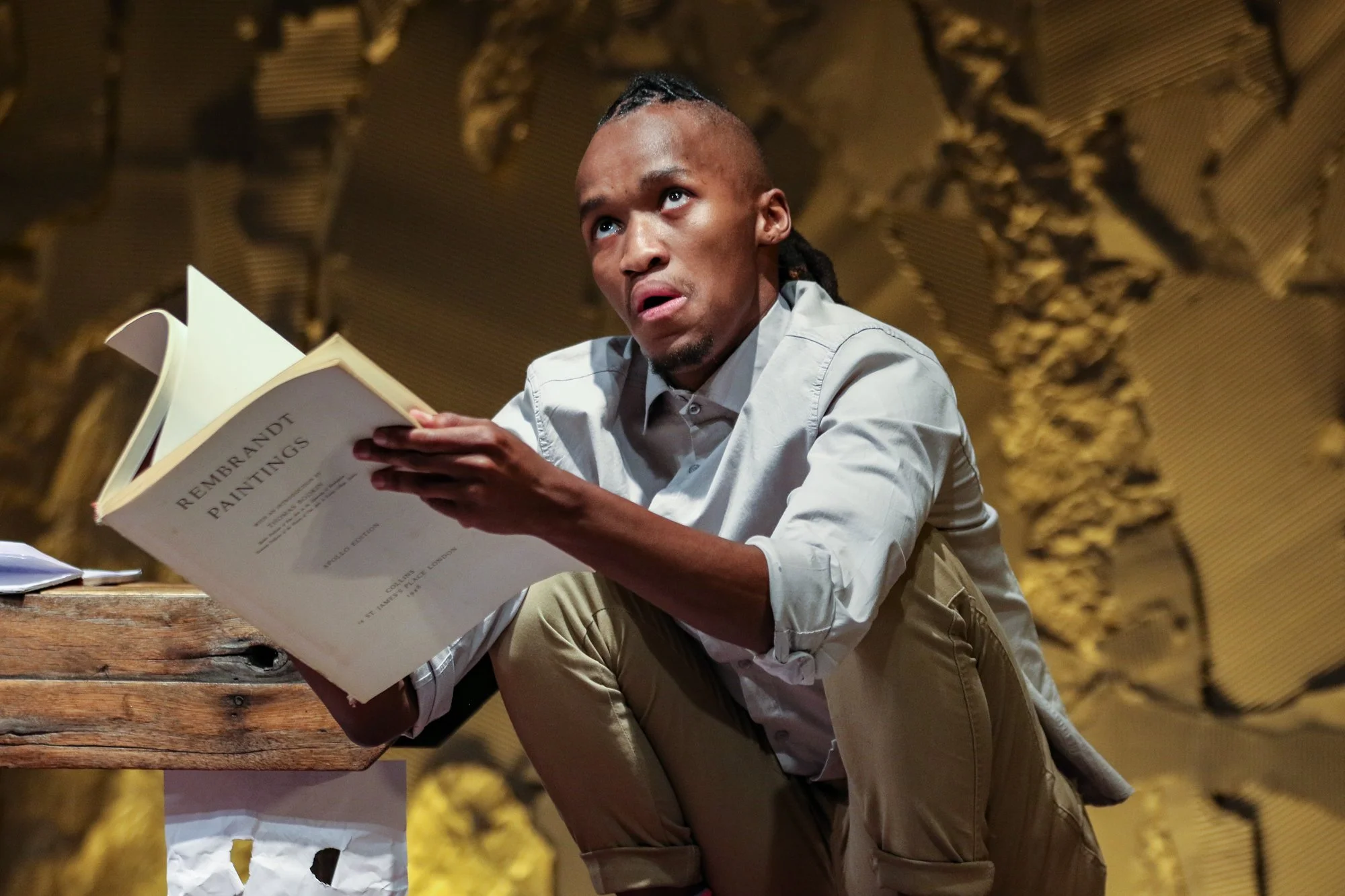

Holding at its core some of The Centre for the Less Good Idea’s interests in language and translation through performance, What Is It? attempts to both satirise and make sense of the varied and nebulous interpretations of mythology as it exists across language, tradition, and culture.

The stage is littered with language and text. Books and loose pages are stacked and scattered around a seat, upon which sits a lone character, played by Sinenhlanhla Mgeyi. One at a time, he picks up these texts and tomes, all of them (seemingly) aiding him in getting closer to the origins, forms, and functions of myth. He spells the word out – m-y-t-h, m-i-t-h, m-e-e-t-h – applies it to a sentence, tests it sound and shape on his tongue. It is a comical and curious scene and one that sets the tone for the rest of the play, an absurd and humorous foray into etymology and history, pursuing all the while the daunting and empirical nature of knowledge.

Giving a physical language to these texts is central to the performance. As Mgeyi engages with a set of dictionaries, he gives them accents, personalities, and physical gestures. It is a means of making sense of a text, applying it across a variety of languages and scenarios to see if it holds, changes shape or meaning. In this way, he is like a student preparing for a test, or making the most of an afternoon bogged down by homework.

In and amongst it all, there is an anxiety of excess. The weight of mythology and language puts him down, drives him to the point of rage. He eats the page, chews the pulp, and spits it out. It is both a consumption of history and knowledge, and an act of pointed refusal.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISERS | Sinenhlanhla Mgeyi & Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu

DIRECTOR | Nhlanhla Mahlangu

PERFORMER | Sinenhlanhla Mgeyi

ISITHUNYWA

A group of people, draped in the uniform of prayer, gather in physical and musical union, rooted in faith. It is a common South African scene and, in Johannesburg, one you’ll see at the riverbanks, in open fields, or even moving through the streets of the inner-city. It is amaZayoni, the ZCC.

In isiThunywa, a performance rooted in the religious practice of amaZayoni, the music, motion, and spirituality of this practice is explored and honoured through performance. An ensemble work that draws on the Season 8 provocations of both breath and mythology, isiThunywa is a piece that is full of movement and musicality. The performers perform in unison, channelling song, text, and physicality.

Like isiThunywa, a universal spirit found in people and nature alike, the piece journeys through time and space. It is a spiritual, representational and mythical journey through a performance that is equal parts climactic and contemplative. Together, the cast are a steady fire, a moveable chorus, journeying towards the light, towards the quintessence of the Spirit-Diviner.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

WRITER & DIRECTOR | Phala O. Phala

CHOREOGRAPHERS | Thabo Rapoo & Muzi Shili

PERFORMERS | Phala O. Phala, Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu, Khanyisile Ngwabe, Sibahle Mangena, Micca Manganye, Muzi Shili & Thabo Rapoo

CHUME AND SUNDE

The simple alchemy of stones and storytelling form the basis for Chume & Sunde, a performance that channels the inimitable imagination and possibility of a child’s story.

Like all good stories, Chume & Sunde is a fictional work that uses factual narrative as a point of departure. In this case, it is the story of Kenya’s Okiek people. A solo work by Siphumeze Khundayi, the performance is delivered as fable, told in the engaging and fantastical style of a child’s tale. There are opposing tribes, courageous children (namely Chume and Sunde), reproachful adults, and a cryptid river monster named Ninki Nanka. At its core, it is tale of love and bravery.

Supplementing Khundayi’s engaging narration is her use of stones. All white and equally sized, the stones become a kind of narrative mapping in Chume & Sunde. They are used to form riverbeds, cattle, the moon and more. Importantly, the stones also serve as characters, charged and animated through storytelling. In addition to activating the blank canvas of the stage, the stones lend a unique tactility and engagement to the work, meeting the audience halfway and inviting them to apply their own projections and impressions of these characters, monsters, landscapes and terrains.

Merging notions of mythology and a contemporary reading of history and culture, Chume & Sunde can be seen as a work that draws and builds on the core components of the theatre – a stage, the simple use of the body and a set of props, and a compelling story.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISER, WRITER & PERFORMER | Siphumeze Khundayi

CHORUS | Thabo Rapoo, Phala O. Phala, Micca Manganye & Muzi Shili

BA MOEPO

Where do lost and uncollected spirits go? Ba Moepo (a Sepedi phrase that means 'those who gravely dig') is a practice-led performance art installation that considers the devastatingly exploitative practice of mining in South Africa, and grapples with labour, extraction, the body, and the earth, post-apartheid. Set in a sparse, yet rich and speculative space beneath the earth, the work honours and draws on the spirits of those lost to the mines.

Ba Moepo is a trying work for viewer and performer alike. It is an installation performance that is both durational and experiential, immersive and compelling. The six men who occupy the stage are more like spectres than performers. They haunt the stage, moving slowly and in silence. Each wears a dim headlamp, illuminating their form, spotlighting their condition. They are trapped together, but remain apart, without the simple respite of human presence to comfort them. Behind them, the harsh, jagged rockface. Above them, the heavy weight of history, labour, exploitation and more. Time moves slowly, excruciatingly. We watch them fall in slow-motion, saliva dripping from mouths contorted in permanent screams. They curl up on the ground, keel over and relent, their bodies breaking and failing.

Conceptualised and directed by Calvin Ratladi, Ba Moepo is theatre as performance art, and as installation. But the audience is made to sit and endure, to watch loss, death, and abandonment in slow motion. As such, much of the activity of the work can be located off stage, in the audience. There is the creaking of chairs, the odd cough or sigh, bodies growing uncomfortable in seats, the shaking of heads, and the rubbing of necks.

Lighting, too, is a key contribution to the work. It can turn the cardboard backdrop to rock, or to gold. Slivers of gilded light or fire shine through from the bottom of the stage, the bowels of the earth. Narrative is held in the body, in the atmospheric soundscape. There is intermittent crying from those on stage. It pierces the silence, hangs in the air like a punctuation mark. At times, it is a total abandonment of hope, other times, a form of raging against it all. Always, though, there is a return to silence and stillness – the loss of breath, the lack of air, the sharp gasp of the mines.

And just as you feel you can endure no more: a single howl, the long and cathartic letting of grief, fear, and abandonment before the slight slowly, very slowly, fades away.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISER & DIRECTOR | Calvin Ratladi

MOVEMENT DIRECTOR | Thabo Rapoo

PERFORMERS | Thabo Rapoo, Nhlanhla Mahlangu, Muzi Shili, Katlego Kaygee Letsholonyane, Micca Manganye & Sinenhlanhla Mgeyi

SONIC DIRECTOR | Nhlanhla Mahlangu

GA RE LEBALA: WHEN WE FOR(GET)

Ritual, shame, and betrayal are some of the themes that are channeled through Ga Re Lebala: When We For(get). It is a simple and impactful performance that unpacks how connection is not something we give or get, rather, it is something that we must nurture and grow.

Two characters occupy an otherwise empty stage. The one wears only a shirt and shorts (Katlego Kaygee Letsholonyane), while the other is draped in jackets, shirts, shawls, glasses and more.

Letsholonyane feels he is lacking. He bows, prays, and seeks blessings. Rapoo, who stands atop a plinth, is hesitant. He regards him with suspicion, but ultimately yields. An exchange occurs – the giving of clothing – and the premise becomes clear. A relationship is established.

Letsholonyane bounds about the stage, trying on his new item of clothing. The novelty wears off, he wants more. Again, the humble request, the gifting of another item of clothing, this time a jacket which is worn proudly. The relationship continues in this way for some time, and with each new piece of clothing, Letsholonyane grows increasingly arrogant, petulant, and ungrateful. Now, he does not so much request his blessings, but rather expects them, demands them. All the while, Rapoo gives and gives, losing clothing, gaining nothing in return.

A harmonica sounds out from offstage and a third character emerges (Micca Manganye). He has come to collect Rapoo. The two leave the scene, slowly enough for Letsholonyane’s guilt and remorse to take hold. He agonises, pleads, strips himself bare. It is too late.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISERS | Katlego KayGee Letsholonyane & Thabo Rapoo

DIRECTOR | Phala O. Phala

MUSICIAN | Micca Manganye

PERFORMERS | Katlego KayGee Letsholonyane, Thabo Rapoo & Micca Manganye

NOT A MACHINE

What kind of connections can be forged between the human body and the machine in motion? In Not a Machine, music, sharp choreography, and the narrative of breath and body are used to probe the duality and the dynamics of these two modes of performance.

From the onset, there is no ambiguity between human (Thulisile Binda) and machine (Muzi Shili). Shili’s movement is sharp and mechanical, Binda’s fluid and free-flowing. A dynamic is soon established, that of instruction. Human commands machine who follows, slowly, but diligently. Human demonstrates, while machine replicates, allowing himself to be corrected, tweaked and tuned.

There is music, then, industrial, percussive sounds that activate the duo. It is here that the dynamic takes on a new shape. Where the human body allows for slight deviations in form, the machine is consistent. When the human slips up, the machine never tires. A question emerges: who does it best? And another: What can the one learn from the other?

Ultimately, there is union. Human instructs machine once more, this time to bend and manipulate his rigid limbs towards an embrace. She tweaks his facial features, codes them into a smile that is almost believable. The embrace is electrifying and stirring. As the lights fade, he winds his arms like a turbine. She circles him, jogs, and gains speed. She runs and runs and does not stop, charged in the way of a machine, a human dynamo.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISER & DIRECTOR | Nhlanhla Mahlangu

PERFORMERS | Thulisile Binda & Muzi Shili

SLEEPWALKING LAND

Taken at face value, Sleepwalking Land is a work containing spoken narrative and physical performance, the former providing context to the latter. What emerges, though, is a more complex relationship between the text, the body, and the endless possibility of the dreamscape.

The story is this: A young boy, Muidinga and his elderly traveling companion, Tuahir, stumble upon an abandoned bus filled with corpses and bits of luggage. As the boy reads to his elderly companion, this central story develops in tandem with their own.

Performed by Calvin Ratladi and Muzi Shili, with narration by Iman Isaacs and live music by Micca Manganye, Sleepwalking Land asks its audience when exactly words lift off the page and present themselves as images in our consciousness. Are they already there, dormant, waiting? Also, are the characters dependent on the text, the reader, or neither?

As Isaac’s disembodied voice guides us through the narrative, Shili and Ratladi engage in their own work of rendering tangible these words and imaginings. They move slowly, wordlessly, out of time with the spoken narrative. A tension emerges and a choice must be made. Does one follow body or text? Is it possible to dip in and out of both, holding these narratives in one’s mind simultaneously?

All the while, Manganye sits just off to the side of the stage, providing a gentle and mesmeric soundtrack, willing these stories to continue. Sleepwalking Land is not a work that provides neat resolution, nor does it embrace the single story. Rather, it is like myth, or dream – inviting speculation and close reading, and always pursuing those divergent routes that might take us out of our ready interpretations.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISERS & PERFORMERS | Calvin Ratladi, Muzi Shili & Iman Isaacs

MUSICIAN | Micca Mangaye

DRAMATURGE | Phala O. Phala

BOLOBEDU

Bolobedu is an intimate two-hander by Ayanda Seoka and Thabo Rapoo that, at its core, interrogates themes of erasure, voicelessness, breathlessness, refusal, and morality.

This is a work inspired by the story of Modjaji, the rain queen often forgotten or erased from history. In Bolobedu, she is remembered and revived through performance. She arrives in a flurry, collapsing onto the stage. Towards the back of the room, there is a drumming which she both invokes and responds to. She calls upon it and she is bound by it. A conversation between body and instrument emerges. It is invocation and instruction, at once breathless and rhythmic.

Throughout this laboured, procedural call and response, Modjaji is a husk of herself. Her breath is laboured and painful. The two meet and begin to populate the stage with grains of rice. It is an engaging scene, equally evocative of a barren landscape and the welcome sound of rain.

Finally, the sky breaks open and rain begins to fall. It is a scene of sustenance and revival, and one that speaks to the impetus of the work – the act of remembering and honouring those ancestral figures, and the growth and nourishment that follows.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISER | Ayanda Seoka

DIRECTOR | Phala O. Phala

PERFORMERS | Ayanda Seoka & Thabo Rapoo

INKOMO

Inkomo, a Season 8 ensemble works, is performance as ritual. The piece deploys an all-women cast to blur and rethink boundaries, roles, functions, and relationships of power and personhood that have been inherited over time.

A single character emerges, donning a grey and white uniform. She considers herself in an invisible mirror, oblivious to the audience before her. A whistling sounds out and the others, all dressed in the same fashion, slowly join her.

She begins to twist and turn, performs a clumsy pirouette. The others flock. They are quick to correct her, to nip and tuck. She arches her back, sucks in her stomach, performs again. It is the first of many collective vignettes, each one mining a sliver of personhood, behaviour, and patterning unique to the individual amongst the ensemble. True to its name, there is much breying and murmuring, the soundtrack to a herdlike movement that both holds and belies a series of striking and singular gestures.

This relationship between the collective and the individual, the private and the public, is the basis for a rich and nuanced performance that pursues, always, a return to balance. Through the work of sharp choreography and slick and intuitive sequencing, the performance is able to hold myriad moments and experiences, each one with its own crescendo and seamless segue.

Alongside the physicality of it all, and running through the work like a resonant chord, is a commitment to collective narrative and musicality.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISERS & PERFORMERS | Zarcia Zacheus, Siphumeze Khundayi, Ayanda Seoka, Sibahle Mangena, Thulisile Binda & Khanyisile Ngwabe

DIRECTORS | Faniswa Yisa & Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu

HASHTAG

As its name suggests, Hashtag performs and plays with culture, ritual, and spirituality in the age of social media, providing a sharp and satirical reading of what we might consider to be a form of contemporary mythology.

The opening of Hashtag is a familiar scene for those who frequent social media. Faniswa Yisa plays the role of a youthful sangoma-turned-influencer, who we meet just as she’s gone live to her loyal online audience. Smartphone in hand, and ringlight nearby, she is pitchy and overzealous, delivering a series of youthful platitudes peppered with slang. She holds up her ‘Black Cocaine’ (snuff) to the camera, talks to us about her communion with the ‘Underground Gang’ (ancestors), and fills the room with ‘Underground Incense’ (imphepho).

In between her monologues, the occasional pan to her sneakers, fresh Nikes from a sponsorship deal. A captive audience in the palm of her hand, she does not once look away from her screen. She boils the pot, steams and brings us along with her, smartphone and ringlight disappearing beneath the blanket. The play’s climax is a literal one – a ‘Yoni Steam’ which sees her straddling the steaming pot, talking to her followers all the while.

Ritual completed, she undoes herself – wig discarded, make-up removed, Nikes placed back in their box to be returned later that day – and allows her true character to emerge. It is the version of herself that she will not allow the world to see. To be a celebrity, though, is to forgo privacy and accept hypervisibility, even when you’re at your most vulnerable.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISERS & WRITERS | Khanyisile Ngwabe & Faniswa Yisa

DIRECTOR | Khanyisile Ngwabe

PERFORMER | Faniswa Yisa

HARD BUT FRAGILE

Hard But Fragile is a work that seeks to find power in brokenness. The sjambok (whip) is used as a tool for instruction, musicality, and performance.

There are three of them – the whips – wielded by two performers. Through these laden optics, there is the constant threat of violence, although it does not emerge, held instead in memory and expectation. The performers, Micca Manganye and Thulisile Binda, engage in a physical dialogue, their engagements short and sharp like the crack of a whip. Outfitted in costumes of brittle, crinkling paper, they flit and shake about the stage like dry leaves.

A sonic swell emerges, the sound of whips cutting through the air and slapping against the stage. When they encounter the body, it is not with force. Rather, they function as tools for performance – loaded metaphors wielded with shrewd physicality. In the hands of Binda, specifically, the sjambok becomes a taut spine, a snare, a tightened bow, even a noose.

Together, the performers duel and converse, developing a duet of raw physicality and incidental musicality that is equal parts severe and poetic.

– David Mann

CREDITS:

CONCEPTUALISER & CHOREOGRAPHER | Thulisile Binda

PERFORMERS | Thulisile Binda & Micca Manganye

MUSICIAN | Micca Manganye

THE WATER TOOK MY BREATH AWAY

Two characters sit beside each other, dressed in funeral attire. “Good morning!” says the man in the suit.

“Yes, I am mourning,” says the woman in the shawl.

It is this kind of absurd, dreamlike miscommunication that gives The Water Took my Breath Away its power. Written and directed by Calvin Ratladi and performed by Faniswa Yisa and Katlego Kaygee Letsholonyane, the play is an abstract two-hander that both prizes and puzzles out the singular effects of a staged dialogue.

The characters are close. They are a married couple, perhaps, or they are roommates. They are close in the literal sense, too. Each on a chair of their own, they sit beside one another for the duration of the performance, bodies pressed up against each other.

They talk in puzzles, each pursuing their own train of thought, while holding the other’s at the edge of their mind, never responding in a linear fashion. They repeat and rework words and their varying meanings. It is a kind of playful attention to wordplay that veers towards obscurity. All the while there is the noise of construction – an elusive antagonist that is always heard, but never quite located – that is the source of their ire.

Throughout their separate monologues, which masquerade as conversation, there is a constant return to claustrophobia, a relentless bombardment of the senses from the outside world. In the wake of a global pandemic and, more specifically, South Africa’s uniquely harsh lockdown regulations, it is a scene that is all too familiar. They are mourning, as it turns out, their breath.

If there is a plot to speak of, it is only hinted at, never fully realised. The lines in The Water Took my Breath Away are there to lure you into the illusion of narrative, guiding you deeper and deeper into repetition, dream, a world built up by linguistic oddities. “This is getting absurd,” says the suited man in one of many short, sharp moments in the play that pokes fun at its own form.

And how do we break this fever dream, this dreamlike state of incoherence? It ends where it began. “Good morning,” says the man in the suit. “Yes,” repeats the woman in the shawl as the lights fade, “I am mourning.”

– David Mann

CREDITS:

WRITER & DIRECTOR | Calvin Ratladi

PERFORMERS | Faniswa Yisa & Katlego KayGee Letsholonyane

DID YOU KNOW?!

For all of its fast-paced humour, Did You Know?! poses a central question: What is the origin and the function of superstition? Performed by Sibahle Mangena, Khanyisile Ngwabe, and Sinenhlanhla Mgeyi, the work explores the absurdity, the mythology and the ritualism of superstitions expressed and practiced over centuries, with a distinct rootedness in South Africa.

The work begins off stage, where bad luck is visited upon an unassuming audience member, activating a chain of events that all carry a loaded, superstitious meaning. A play that’s full of physicality, the cast also develop a neat choreography around these superstitions. They jump across the room to avoid stepping on a crack, contort their bodies around a ladder to avoid passing under it, and then do away with the ladder altogether for fear of following in the same path as the person ahead of them.

The three friends chase good luck and avoid ill-fortune at all costs. They chastise each other for their ignorance, warn one another against certain gestures or cultural faux pas. “Don’t whistle inside the house!” they cry. “You must never point at a grave with your finger!” they warn. As to the sources of these superstitions, none of them can say. What they are certain of, though, are the consequences – bad luck!

– David Mann

CREDITS:

DIRECTOR | Iman Isaacs

PERFORMERS | Sibahle Mangena, Khanyisile Ngwabe & Sinenhlanhla Mgeyi